The beekeeping year has begun. Inside the hive the bees are preparing for winter. The queen lays fewer eggs, drones cower as their sisters evict them from the colony, and gaps in the nest are stuck fast by sticky red-brown propolis.

Foragers leave the hive early in the morning and return in the fading evening light. Their bodies are sprinkled with pollen and abdomens heavily laden with nectar. The queen and her workers are getting ready to begin all over again in spring, but first they must cosy themselves in a snug winter nest filled with the final drops of the season’s honey.

Of course, this seasonal activity varies with location, climate, available forage, and the situation within individual hives, but traditionally this is the picture of the start of the beekeeping calendar. On a recent holiday to the countryside, I saw plenty of bees (honeybees, bumbles and solitaries) out and about. On our return, the garden was buzzing with honeybees drinking from a bush with clustered dark-pink flowers like the last of the summer wine.

In my kitchen, the honey crop has been settling since Emily and I did the hard work of extracting a few weeks ago. In past years, our bees have made honey that was difficult to spin out in the extractor, but which didn’t take much filtering. This year the honey spun out fine, but it has required more time to settle, strain and filter.

For a few days, our harvest sat in storage containers to let air bubbles and lighter particles float to the top, and larger debris sink to the bottom till the froth, or ‘marmalade’, could be scooped off. When it was ready, I cleared the kitchen table and got out the buckets, muslin cloth and string to start filtering.

We had extracted the supers in three batches – the third batch being from Emily’s allotment hive – because it’s nice to bottle the honeys separately according to their unique taste and fragrance. Pepper’s crop smells of dark forests and Melissa’s harvest has an aroma of berries-and-lime.

The honey from Pepper’s and Melissa’s hives was first strained using fine muslin tied around two buckets with string. A wire mesh strainer also filtered out the honey that had pooled around the wax cappings.

With two buckets full, the air bubbles were still rising. I left the honey to settle for a second time, before scooping off the froth again, and filtering into jars to be bottled. I always use mini jars to make the honey harvest spread further, and keep it stored in a cool kitchen cupboard.

Most honeys crystallise over time as networks of crystals eventually form from the heavy concentrations of dissolved glucose suspended in the solution, though this process can vary from a few days to several years. I have one jar of Myrtle’s honey left from last year that still hasn’t crystallised.

Honey extraction, filtering and bottling is a lot of work for the hobbyist beekeeper, and even more work for the commercial beekeeper. For that reason, the leftover wax cappings and other gubbins have been set aside in mini buckets to clean up on a rainy day.

My kitchen surfaces and equipment were scrupulously cleaned, and I was careful to not to contaminate the buckets, jugs and jars with any drops of water. As Andy Pedley told me once, “Water is the enemy of honey.” However, if I were to sell honey, then I’d need to be more fastidious about the whole operation from straining and filtering, to filling each bottle to the exact amount stated on the label. My family and friends might appreciate a jar of my honey, a true taste of home, but it wouldn’t win any prizes at the national honey shows!

For the full legislation of the preparation and sale of honey, you can read the updated The Honey (England) Regulations 2015 on the government’s website.

The clean-up afterwards is almost as much work. Hot soapy water and towels to wash down and wipe clean sticky work surfaces, tables and equipment at least three times, but it was worth it!

At the apiary, the beekeeper is also preparing the hives for winter, and there are many things to think about. Is the queen laying well enough to take the colony through winter and to build up again in spring? Does a smaller, weaker hive need to be united with another colony to make a stronger hive for overwintering, with the provision there is no disease? Is the colony healthy and does treatment need to be given for varroa? Does the colony have sufficient stores or does it need feeding syrup before the end of autumn? Is the hive equipment in good order with gaps in the wood sealed and mended, entrances reduced against robbers and pests, and guard against woodpeckers and mice ready to put on? Are the supers staying on the hive or do they need to be cleared and removed for safe storage against wax moth?

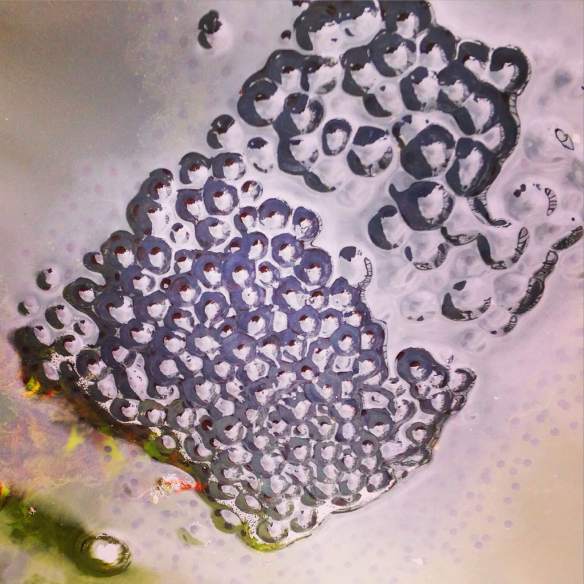

Yes, quite a lot to consider, but most importantly is thinking about how to enjoy the last couple of months spent with the bees. Here’s Melissa’s hive with Emily removing the second tray of Apiguard after the workers tried to stick it to the top bars with propolis.

After a long session of afternoon tea with the Ealing beekeepers, the smoker was lit, with some tips from Pat, and Emily and I were off to inspect our two remaining hives. The beginners had already checked Pepper’s hive, spotted the queen, and found a very high number of varroa mites (almost 600) on the board. This may be due to Apiguard treatment, but it is still disappointingly high. The only positive is that it is better to have varroa mites dropped onto the monitoring board, as a result of varroacide treatments, than in the hive.

Peppermint’s colony was calm and well behaved. These busy bees are rearing new brood like summer is here to stay, and the queen was spotted walking nicely across the comb. The hive is rather low on stores. We didn’t take any honey off of this hive, but it may benefit from autumn feeding after the Apiguard treatment. The mite drop so far is around 100, a lower number is to be expected from a newer artificially swarmed colony.

Melissa’s colony is strong and well, and the queen was found with her head in the comb searching for suitable cells to lay her eggs. Signs of unsuccessful attempts to overthrow the queen by the workers remain. It looks like Melissa will lead this hive into next spring.

We spotted workers with yellow-splashed faces, perhaps from head-butting pollen into cells or from a flower they had visited (sorry for the blurry photo above, fortunately Emily’s finger is pointing to a worker with yellow warpaint). The white-striped Himalayan balsam foragers were also making their way through the colony.

We closed the hives with records written and plans discussed for the start of the season ahead.

Autumn mists have been falling on roofs and tree tops early in the morning this August. Yet, autumn is my favourite time of year, and in many traditions it is a time to clear out the old and to make space for new things. I can’t feel too sorry for the end of summer, only excitement for the inspiration that autumn will bring.